ePhyto: A Global Solution to Make Trade

Safer, Fairer, and More Fraud-Resistant

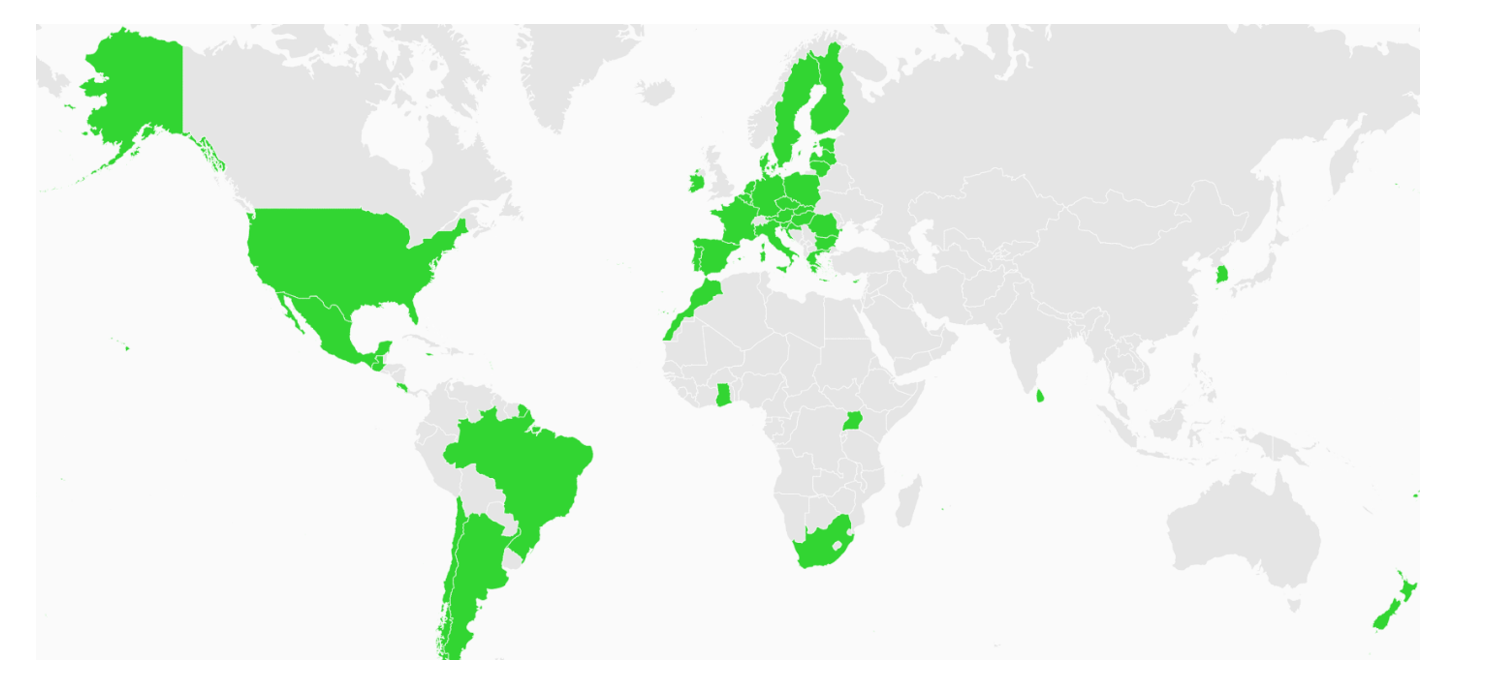

Many nations (in green) have implemented the ePhyto Global solution. Canada, and many more are in the process of developing the ability to exchange “ePhytos”—electronic plant health (phytosanitary) certificates.

Many nations (in green) have implemented the ePhyto Global solution. Canada, and many more are in the process of developing the ability to exchange “ePhytos”—electronic plant health (phytosanitary) certificates.

What is the plant health threat to North America?

One of the biggest challenges facing agriculture and forestry today is how to move billions of dollars’ worth of plant commodities in international trade without accidentally spreading invasive pests and diseases, and with the safety that such commodities meet the importing phytosanitary requirements supported by a phytosanitary certificate. To keep trade safe in North America and around the world, countries inspect and certify that their plant and plant product exports meet the importing countries’ phytosanitary requirements.

That certification is critical because meeting the importing nation’s phytosanitary requirements minimizes the risk of introducing and spreading a potentially devastating plant pest or disease into that country. But today, most phytosanitary certificates are issued on paper, a vulnerable physical item.

What is at risk?

Phytosanitary certificates must travel long distances to arrive with the shipment, and many people must handle them. Valuable shipments—sometimes perishable—can sit for long periods at ports of entry if the paper phytosanitary certificate is missing, damaged, incomplete, or fraudulent. Importers can incur costly delays and possible charges for storage at the port. In addition, the importing country does not have a guarantee of the commodity’s phytosanitary condition.

In addition, a country that allows a commodity to enter without a credible, accurate certificate puts its agricultural and forestry production systems—and its people’s food security—at risk from the introduction and spread of damaging invasive pests and diseases. That is an alarming prospect because trade of plants and plant products has become crucial for human survival and economic growth in many rural areas. This trade is worth nearly $1.7 trillion annually, according to the United Nations (UN). Over the past decade, this growth has almost tripled. Thriving plants mean thriving people.

Invasive pests—which phytosanitary certificates and many other measures are intended to stop—destroy up to 40 percent of food crops worldwide, and cause $220 billion in trade losses annually, the UN estimates. They can also throw ecosystems out of balance and devastate biodiversity. As we know, invasive pests can spread through global agricultural and forestry trade, and this pest pressure constantly increases.

To feed the world’s growing population, agricultural production must increase by about 60 percent by 2050, according to the UN’s estimates. That means we must do everything we can to protect plant health regionally and internationally from destructive invasive pests.

Where does the threat originate?

In global trade, a pest anywhere can travel to just about any suitable habitat around the world—if plant products are not inspected and their phytosanitary certificates are not verified. Import requirements and phytosanitary certificates are part of the tools used by countries to stop the introduction and spread of pests. Missing, damaged, incomplete, or fraudulent certificates jeopardize that critical check.

How can the threat get to North America?

Imported commodities can move by sea, air, and land. Canada and the United States, and Mexico and the United States, share long land borders in North America. Often agricultural commodities from Mexico transit the United States en route to Canada, and vice versa.

How has the international community responded?

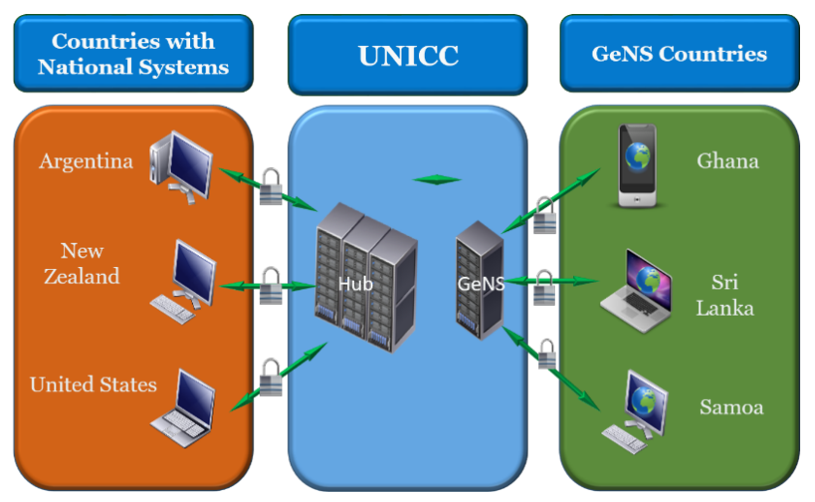

The new global ePhyto system is an interconnected electronic certification exchange system for trade.

Since 2015, the International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC), with support from countries around the world, has been developing and implementing the ePhyto Hub. The IPPC is an international plant health agreement with 184 contracting parties (participating countries). The agreement aims to protect the world’s plant resources from the introduction and spread of pests, and to promote safe trade.

In 2019, the IPPC launched the ePhyto Hub, which allows countries to exchange fraud-resistant, electronic phytosanitary certificates called ePhytos. That same year, IPPC also released the generic national system called “GeNS” that lets any country without a national electronic certification system access the Hub.

Today, 44 countries are exchanging ePhytos through the Hub, helping to make agricultural trade safer, fairer, and more fraud-resistant. About 50 countries are in the process of connecting their national systems to it, and more than 50 others are working to obtain GeNS.

What is NAPPO’s response?

Each member nation of the North American Plant Protection Organization (NAPPO) has taken big steps to ePhyto implementation. NAPPO’s ePhyto Expert Group is assisting and providing technical support to the IPPC ePhyto Steering Group. Christian Dellis, from the United States’ national plant protection organization (NPPO), chairs both the IPPC’s ePhyto Steering Group and NAPPO’s ePhyto Expert Group. He has been showcasing ePhyto at NAPPO’s annual meeting and in other venues around the world through live demonstrations of electronic certificate exchanges.

“In the NAPPO ePhyto Expert Group, we’re sharing lessons learned in ePhyto implementation and discussing the latest IPPC updates,” Dellis said. “Mexico has a national system that is connected to the Hub, and they are accepting all U.S. ePhytos. The United States is accepting many of Mexico’s ePhytos, and that number keeps growing. And over the last several months, we’ve held several calls with Canada to provide technical advice as they build their system.”

Dellis notes that Mexico and Canada receive more than a quarter of the United States’ phytosanitary certificates. In 2020, Mexico received 86,000 of them, the most of any nation. Second is China with 59,000, and a close third is Canada with 58,500.

“For U.S. industry, exchanging ePhytos with Mexico will be a tremendous cost and time saver,” Dellis explained. “Before COVID-19, when a shipment departed the U.S. Gulf ports for Mexico, someone would need to fly to Mexico to deliver the paper certificate at the port of entry because the cargo moved faster than mail, and the shipment couldn’t begin discharging without the original certificates. Those travel costs and hours add up.”

Although shipments imported into the United States still need a paper phytosanitary certificate, fully paperless exchange is almost a reality. For example, when there’s a problem with the paper certificate at a U.S. port of entry, the U.S. NPPO will validate it using the ePhyto version if available, speeding the shipment’s entry into the country. In the near future, the United States should have the ability to send ePhytos directly to U.S. Customs agents. Then imports can become truly paperless in the United States.

“With COVID-19 and all of its challenges, the importance of electronic documentation has never been more apparent,” Dellis said. “It has boosted the number of countries taking action to get up and running as soon as possible. Countries that can exchange ePhytos have realized a great benefit during the pandemic.”